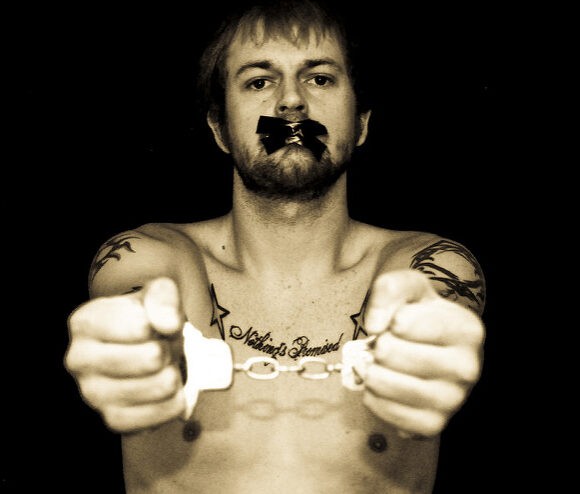

Internet Is Censored in Two-Thirds of the World

Many believe the Internet equals freedom of information. Recently, that has been less and less the case.

Maung Saung Kha, a 23-year old poet from Myanmar, was relieved last May to hear that he would be released from prison. On 24 May 2016, Mr Saung Kha was sentenced to six months in jail for defaming Myanmar’s former president Thein Sein, but because he had already spent six months behind bars, he was freed the same day.

His crime: posting a poem on Facebook in which a newlywed was baffled to see a tattoo featuring Myanmar’s former president on her husband’s genitals. The husband in the poem was Mr Saung Kha. In other parts of the world, such a poem would trigger a smile. But in Myanmar, authorities took this seriously. Using provisions on defamation from the telecommunications law, they justified imprisonment of the young bard in the Insein jail near Yangon, Myanmar’s capital city.

Mr Saung Kha thus became one of Myanmar’s first political prisoners to be sentenced since Nobel Peace Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi took power last April.

But Myanmar is not a singular case. Authorities worldwide are becoming increasingly averse to criticism in whatever form it may occur: poems, articles, jokes or petitions. Astonishingly, two-thirds of internet users live in countries where criticism of authorities is subject to censorship, according to Freedom of the Net 2016, a survey of internet freedom in 65 countries worldwide, run by Freedom House, a U.S. government funded NGO.

Social Media Allergy

Internet freedom has declined for the sixth year in a row, according to Freedom House. Increasingly, governments target social media and communication apps in their attempt to prevent the spread of information. In 24 of the 65 countries canvassed by Freedom House, the government impeded access to social media and apps. The countries covered in the Freedom House survey shelter 87% of the globe’s population.

In many cases, people are punished for petty offenses. A Facebook user in Lebanon was interrogated by the country’s cybercrime watchdog for criticizing a singer. Often, punishments are disproportionately severe. A Saudi was put behind bars for 10 years and received 2,000 lashes for spreading atheistic thoughts on Twitter.

Criticism or mockery of authorities has serious consequences. A pastor in Zimbabwe was arrested last July for criticizing the country’s leadership on YouTube. In Hungary, 17 people were charged with defamation simply for sharing a Facebook post about some allegedly illegal financial dealings of a mayor in a Hungarian town.

No Sensitive Issues, Please

Topics authorities are most allergic to include the LGBTI (Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-Transgender-Intersex) community, political opposition, activism online and satire. Attempts to censor LGBTI-related content were observed in 18 countries ranging from failed states like Sudan to politically unstable regimes such as Azerbaijan and Turkey to stable democracies like South Korea. Political opposition is abhorred by authorities in 40% of the countries in the Freedom House survey.

Corruption is also among the sensitive topics that can lead to takedowns, blocking or arrests. The Malaysian government went so far as to block an entire international content-sharing platform in a move to restrict access to information about a corruption scandal involving the country’s premier Najib Razak. Medium, a platform spawned by Twitter co-founder Evan Williams, was completely blocked there after some local websites that slammed Mr Razak began to publish their articles on Medium.

Growing censorship online is worrying as the internet has become the main medium for critical content, including investigative reporting, comments and exchanges.

Most of the major investigative stories in the past five years were broken by groups and journalists whose work mainly circulates online. In Hungary, most investigations appear online. In a recent development, a team of reporters from the online news portal Index.hu broke a major story about widespread corruption in the government led by Viktor Orban. The investigative team worked for nearly a year on this story. Independent news organizations in Indonesia and the Philippines have increasingly been faced with content blocking online. The Southeast Asia Press Alliance (SEAPA), a Bangkok-based NGO, has documented a slew of internet media crackdowns in the region over the course of the past four years.

In China, as the government has stepped up efforts in recent years to clamp down on investigative journalism, reporters broke away with their news organizations and set up shops online. Veteran investigative reporter Luo Changping of the Caijing magazine turned to the internet to publish his investigations into dubious financial dealings of local officials. However, that cost him his job as editor at Caijing. China was declared by Freedom House “the year’s worst abuser of internet freedom.” President Xi Jinping’s information policy has led to dozens of prosecutions for online expression. Those spreading rumors online, for example, risk seven years in prison in China.

What the internet has been going through during the past six years is discomforting for freedom of expression activists, many of whom hoped the internet would become the main space for free speech. Instead, it is becoming a restricted space where authorities sanction people they decide are too outspoken.

Photo: Elias Bizannes