The Key Media Owners in Romania Have All Fell Foul of Law

They started television stations two decades ago and acted as the “merchants of hope” as they were selling glittering realities Romanians were craving for. More than 20 years later, television in Romania is an affair blemished by scandals, pressures and unlawfulness.

Organizations such as Freedom House or Reporters Without Borders continue to rate Romania high on the scale of media freedom. This is not necessarily inaccurate if one looks for example at access to information and freedom of speech. And yes, in theory, any honest journalist can enjoy full professional freedom if they write on their blog or on a few alternative platforms. They might also enjoy freedom in mainstream media, but only until they intersect with the interests of media owners. That is the true limit of Romanian media freedom.

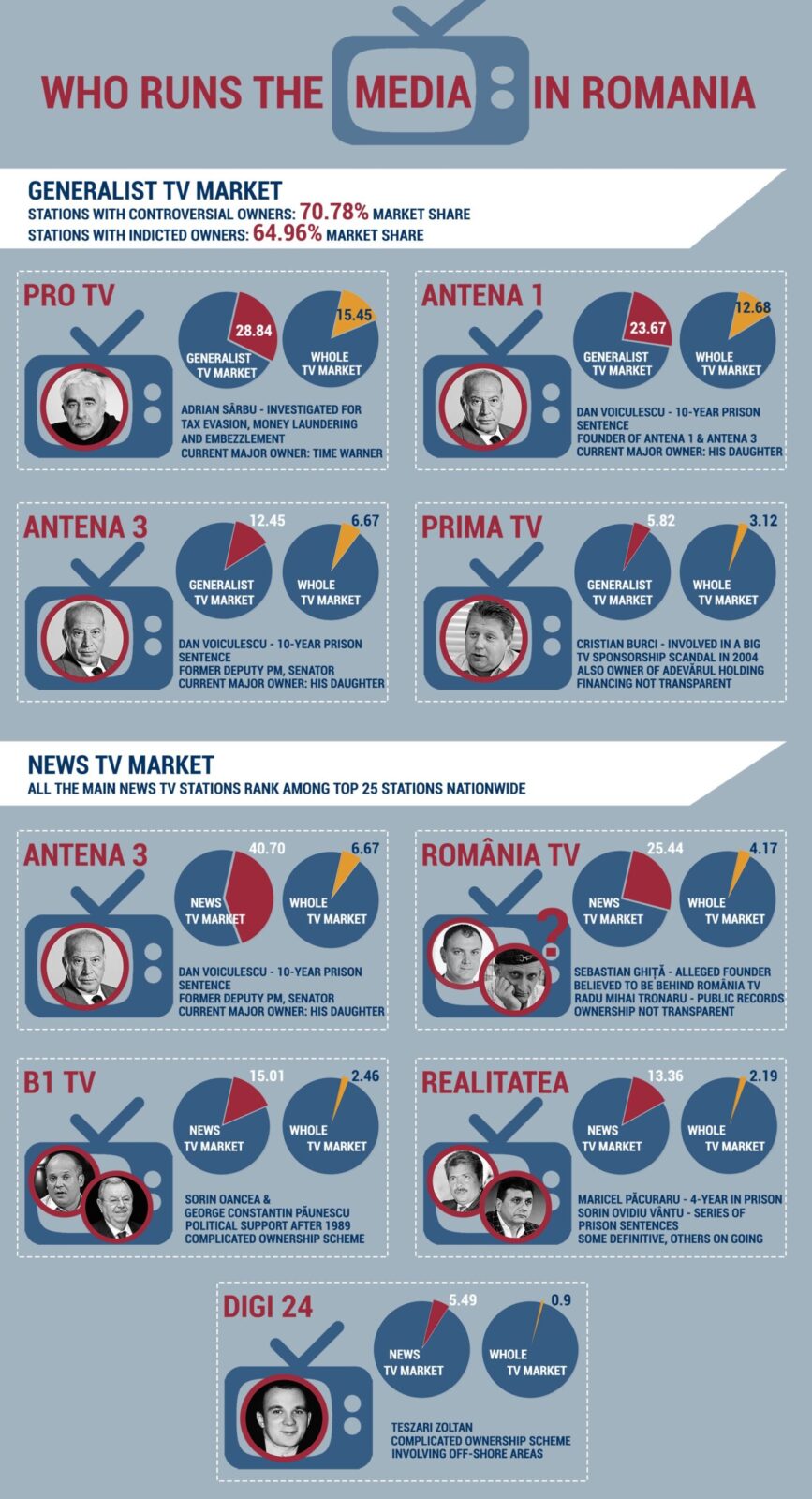

But who are these owners? Their history harks back to the 1990s when a group of people with stained communist pasts and ties to the former secret police of the communist regime began to pump their cash into television. What they have built since then is a media system geared on protecting economic and political interests. They built this system often illegally. Many of these owners have been jailed or are in courts for a bevy of indictments.

Looking back, much of what Romanian media is today has been shaped by one man, Adrian Sarbu, a local entrepreneur who founded one of the first private TV stations in Romania, according to the first release of “The men who bit the watchdog”, a study of the newly established London-based Centre for Media Transparency.

The American Dream in Eastern Europe

Ronald S. Lauder’s vigorous ventures in television in Eastern Europe back in the 1990s were met at first with great hope. An heir to the Estee Lauder fortune and a former U.S. ambassador to Austria in the late 1980s, Mr Lauder promised a chance to see a new world, an opportunity to experience the American dream from one’s home. To be sure, this reaction was entirely natural. After 50 years of communism, people in the region were hungry for normality and prosperity, for free information and quality television programs. Mr Lauder`s broadcast operator Central European Media Enterprises (CME) offered back then the opportunity to make all these dreams come true.

Romania was no exception from the rest of Eastern Europe. Immediately after 1989, an immense media enthusiasm took society by storm. Thousands of publications of all types and shapes appeared overnight and all things seemed to be heading in the right direction: a vibrant and free media market. The private station that changed the game was Pro TV. It was the child of Lauder`s CME and of local media businessman, Adrian Sarbu. It came with glitzy news studios, swank reporters, sensationalist stories and American blockbusters.

Two decades later, the Romanian story has finally met its twist. The promising media landscape has been reduced to an impossible structure that offers maximum freedom, but only within the limits of its ownership. Access to information and freedom of speech are values respected mainly in fringe publications and internet outlets. The mainstream media, those that command millions of eyeballs, are captive to its owners. And most of these owners have been sentenced to jail or are currently facing criminal charges. How is that for a story twist?

Breaking the Law

The Romanian mainstream media began with just a handful of people. Albeit financially weaker than their western counterparts, these mini-tycoons were nevertheless decisive in shaping the Romanian media landscape as we see it today. Their business success (expressed in ratings and advertising dominance) had destructive consequences for media freedom and was often followed by a raft of legal problems.

Explaining this path of development is difficult, but by no means impossible. One has to look at media as part of the larger post-communist context. These local media tycoons generally had complicated communist pasts, links to the former secret police and large amounts of money they made in the early 1990s. They were never really visible. They bragged to be merchants of hope and transparency. Hope, because television in those early days after 1990 gave everybody the illusion that they can change their lives by simply appearing on the screen. Examples of kids coming from poor families who became rich by being part of TV shows abounded. Sparkling TV series or shows featured people amassing wealth through duplicity and crookery. But behind all these operations there was a thicket of secret business structures.

Evidence of this Byzantine system of hidden interests was uncovered when criminal investigations into media owners began to pile up in recent years. They were then followed by criminal charges against media groups as well.

Mediafax Grup is currently being investigated for money laundering, Antena TV Group and Intact Publishing are being investigated for blackmail and Realitatea Media is being investigated for money laundering. These companies essentially control the bulk of television audience and television ad spending in Romania. One by one, owners behind media groups, Adrian Sarbu, Dinu Patriciu, Sorin Ovidiu Vantu and Dan Voiculescu have all been faced with criminal charges. Mr Sarbu of Mediafax Grup was placed under preventive arrest in February 2015 as a criminal investigation was launched into accusations of tax evasion, money laundering and instigation to embezzlement. Mr Patriciu, who controlled another big media group, Adevarul Holding, died in August 2014 before a final court ruling in a lawsuit against him was made. Mr Vantu and Mr Voiculescu both received jail sentences in the past.

However, much of the media market history in Romania has been shaped by one person, Mr Sarbu.

A Made-up Success Story

Mr Sarbu, immediately after the collapse of communism in 1989, founded one of the first private news agencies in Romania, Mediafax, which today is the main news provider for the media in Romania. As the market was half-closed to foreign investors, major foreign players needed a local partner to obtain and hold the operating license. The law didn’t allow foreign entities to hold a broadcast license. Hence, Mr Sarbu served as the local partner for Mr Lauder and his CME. The duo launched the company’s first TV station in Romania in the early 1990s, Pro TV. The station became number one in both audience and advertising share and, eventually, its success propelled Sarbu to the position of CEO at CME many years later, in 2009.

The media history of Mr Sarbu is not an ordinary success story. In fact, Pro TV and the rest of his media ventures have been for the most part of their existence debt-laden as they failed to pay back taxes. The companies Mr Sarbu managed survived mostly thanks to the government. Back in then 1990s, the government agreed to reschedule or even cancel some of Pro TV’s tax payments. The price paid by Pro TV for that was positive coverage. This method of survival was mimicked by many other media companies. The state widely used such fiscal clemency as well as state advertising as tools to control media in the early 2000s.

Thus, at the end of the day, all these media ventures were in no way real success stories. In the end, both Mr Lauder and Mr Sarbu left CME. Following severe financial problems, the company was taken over in 2014 by its primary shareholder, Time Warner, and is now being restructured. Pro TV remains the leading television station in Romania by ratings and advertising share, but its dominance from the early 1990s is long gone.

But Mr Sarbu’s legacy remains. Television in Romania is unlikely to develop any further in the near future. The biggest hope for change comes from the telecoms industry where new TV projects are being concocted.

Visuals: Ioana Moldovan, Euractiv.ro