Why Himal is Leaving Nepal

Himal has been in business for three decades. Now it is folding, and Nepal’s authorities have a problem.

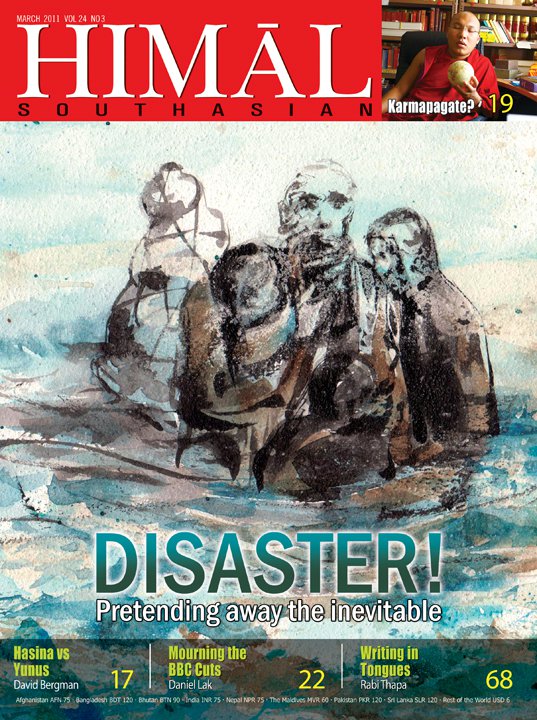

The end of summer got very heated for Himal Southasian, an English in-depth journalism magazine covering the South Asia region from a newsroom in Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital city. The publication announced that it would suspend operations by November 2016 after nearly three decades in business.

The closure was prompted by the failure of local authorities to process papers that would allow Himal Southasian to operate legally. More precisely, the Nepalese government prevented the magazine from accessing grants that they received from foreign donors. Organizations in Nepal that are funded by foreign entities have to apply to the authorities for a permit to access these funds. Only then can foreign groups wire cash to them.

Himal Southasian has been waiting for approval to access a grant from a U.S. donor for more than half a year. Without any response from the authorities to when and if this approval would be granted, they decided to fold. The publication simply didn’t have any more resources to continue its work.

The Art of Legal Silencing

Some might think that the blame for the lengthy approval process lay squarely on the incompetence of Nepal’s local bureaucrats.

In fact, it has more to do with politics.

Some of Nepal’s authorities simply don’t like the publication and its supporters, some of whom are outspoken critics of the regime. In a note about Himal’s closure released at the end of August 2016, the board of Southasia Trust, the magazine’s publisher, wrote that unnamed “powerful state entities” made pressures to take Himal out of business in spite of the fact that Southasia Trust was fully compliant with the country’s laws. Various government officials have admitted this privately.

“Himal is being silenced not by direct attacks or overt censorship, but the use of the arms of bureaucracy to paralyse its functioning,” Southasia Trust wrote.

The authorities’ campaign to silence Himal Southasian has been ongoing for some three years now, but it intensified during 2016. Not only funding from abroad was restricted. Work permits for journalists and editors that the magazine planned to bring from abroad were not given. Payments for writers from outside Nepal were unreasonably delayed.

Moreover, Kanak Mani Dixit, Himal’s founding editor and Southasia Trust’s current chair, was continuously harassed by authorities for more than a year. Last April, he was arrested by the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA), Nepal’s anticorruption watchdog. Mr Dixit said that this was a personal vendetta of the CIAA’s head, Lokman Singh Karki. Mr Karki is a controversial character in Nepal. For example, he is remembered for his involvement in crushing a pro-democracy movement back in 2006. His appointment in 2013 stunned the country’s intelligentsia and democracy activists.

Rising From the Ashes?

Himal Southasian is published in print as a quarterly magazine. It also runs its own web portal. Besides that, the Southasia Trust also organizes a biennial documentary film festival in Kathmandu as well as conferences on cultural issues.

Himal Southasian is the sole regional magazine covering the entire South Asia region, stretching from Afghanistan to Myanmar and from Tibet to the Maldives, a vast market of more than 1.4 billion people. With its in-depth journalism in the form of analysis, commentary and op-eds on regional trends in politics and economy, the magazine mostly caters to a highly educated readership. In the past, it covered issues such independent media, food security and labor.

Himal’s editor, Indian-born Aunohita Mojumdar, hopes the publication can be relaunched when the political context in Nepal will allow that, or resume the editorial work from elsewhere in South Asia.

Ms Mojumdar has worked in very difficult places before – in the 2000s, she freelanced in Afghanistan. Her work appeared in the Guardian, the Christian Science Monitor and Times of India.

The closure of Himal has much deeper implications for the state of journalism in Nepal. The country has been a leader of free press since democracy started in 1990. But the mess in its political life in the past years has badly hurt independent journalism.

Himal’s leaving is a sign that journalism is in an agonizing state in Nepal; and that is just the beginning.